A minute saved is a minute earned, while a minute wasted turns into wasted months full of headaches

(Disclaimer: my memory of the story in this post could be totally wrong. But it still makes a good story. Maybe.)

For years, Yahoo! used a fork of Bugzilla for internal bug and issue tracking. (They may still, for all I know.) Like many highly-customized software forks, the code base would increasingly diverge from the public version over time. At some point while I was there, the internal team supporting Y!’s Bugzilla installation merged back on the open-source trunk, which was likely no small feat, given the accumulated changes on both sides.

I honestly don’t remember what new shiny stuff may have shown up, both because this event happened a number of years ago, but more importantly, because of one thing the update removed: the “assign this to me” button.

Here was a typical workflow for engineers before the change: someone files a bug against one of the components their team owns, they get an email, they go to Bugzilla, look at the description, and then click the “assign this to me” button. With one click, they would become the ticket owner.

Here’s what that engineer’s exact workflow became after the change: someone files a bug against one of the components their team owns, they get an email, they go to Bugzilla, look at the description, and then click the “assign this ticket” pulldown menu, which contains the emails of literally 1000s of Yahoo! employees. They could then move to the keyboard and start typing their email address to narrow the selection or keep scrolling, or go back and forth, until their email address showed up and they could click on it. Then they had to go hit the page update button.

I personally knew countless people (ok, at least three) who opened an issue in Y!’s Bugzilla (of course) against Y!’s Bugzilla requesting the return of the “assign this to me” button. And the owning team closed every single one with that most passive-aggressive of Bugzilla statuses: WONTFIX. One of those WONTFIX recipients told me the person who closed his ticket did add a note that they may look at adding the button back during the next quarter’s planning. (Actually, I think I heard one was closed with that other of most passive-aggressive Bugzilla statuses, WORKSFORME, but anyway.)

If this story makes you think, “yeah, that would probably be a little annoying, but it’s just one button, no big deal,” then look at it another way.

Let’s assume the one-click method took one second per use, while the alternative took 10 seconds.

| Actions | Total time before change | Total time after change |

|---|---|---|

| One engineer claims one ticket | 1 s | 10 s |

| One engineer claims 12 tickets / day | 12 s/day | 2 min/day |

| One engineer claims 12 tickets / day over 5-day work week | 1 min/week | 10 min/week |

| 1000 engineers (this was old school Yahoo!, people) each claim 12 tickets / day over 5-day work week | 16 hrs 40 min/week | 6 days 22 hrs 40 min/week |

| ^ over 3 months, assuming that team was actually going to fix it the next quarter | DO YOU SEE WHERE I’M GOING WITH THIS? | DO YOU??? |

Hopefully we can all agree that this situation is just going to be a forever-snowballing waste of time, no? But the clockwise metric belies a potentially more destructive cost. This user interface change had created visceral, widespread frustration through almost every single engineering team in the entire company. And given the point in Yahoo!’s history, during the Year of Five CEOs (I still want a t-shirt that says “I Survived the Year of Five CEOs at Yahoo!”) when everyone was already coping with high levels of frustration and uncertainty within the company (I think this was also the year of five re-orgs), this kind of regression added more dysfunctional fuel to the bonfire.

I don’t know if there’s a popular or accepted term for the foil of a “force multiplier,” but I’m going throw a few out there: inertia generator, force denier, effort black hole. Every engineering org has tools or processes which could benefit from an investment of time and effort to simplify their use and speed up tasks, of course. And well-managed, empowered organizations will have time to invest in their improvement, but every team has competing priorities, a to-do list, and a finite amount of resources. You want to try to divvy up the resources you have where they will provide the biggest bang for the buck. Sometimes those dividends are delivered purely in time or money (and time is money), but you need to keep an eye on other metrics that are not generally measured outright in any team (at least none that I’ve seen), but which are also critical indicators of how well an engineering team is functioning at a given moment.

Someone else can probably offer a more business-friendly euphemism, but frustration is a major, though usually indirect, indicator of how well and efficiently a team is functioning. Predicting the net gain or loss of time savings for any given change seems pretty straightforward in most cases. And really, engineers and product managers who pay any attention to and have real empathy for their peers and users should also be able to give a rough estimate of the net change in frustration generated by a given software (or process!) change.

I think of engineering frustration as a mental tax that employees pay out of their own mental pocket and that generally no company reimburses. It wastes time and energy, but worse, when its sources are not addressed, it can create mistrust or animosity between teams (“They’re making my job harder because they aren’t doing theirs!” or “I guess management doesn’t care that we’re constantly wasting time on this.”, etc.) Ongoing, unaddressed frustration will poison your engineering culture.

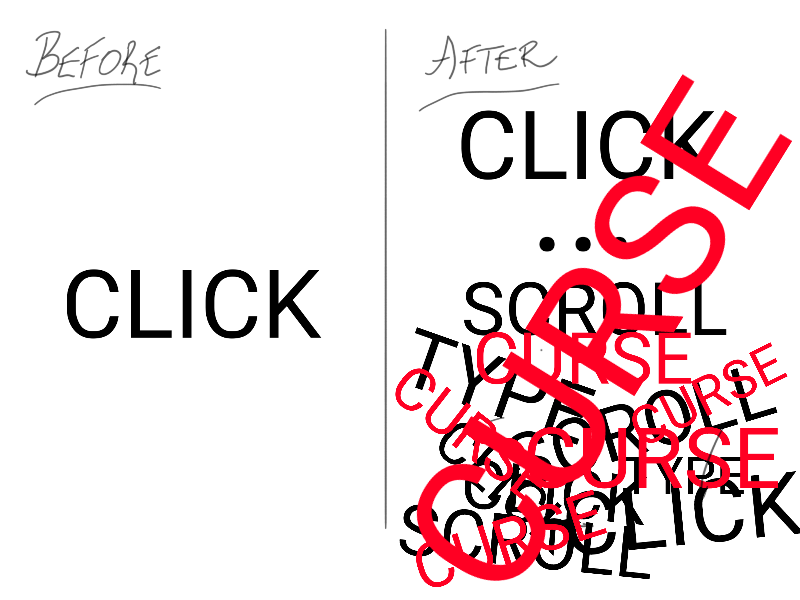

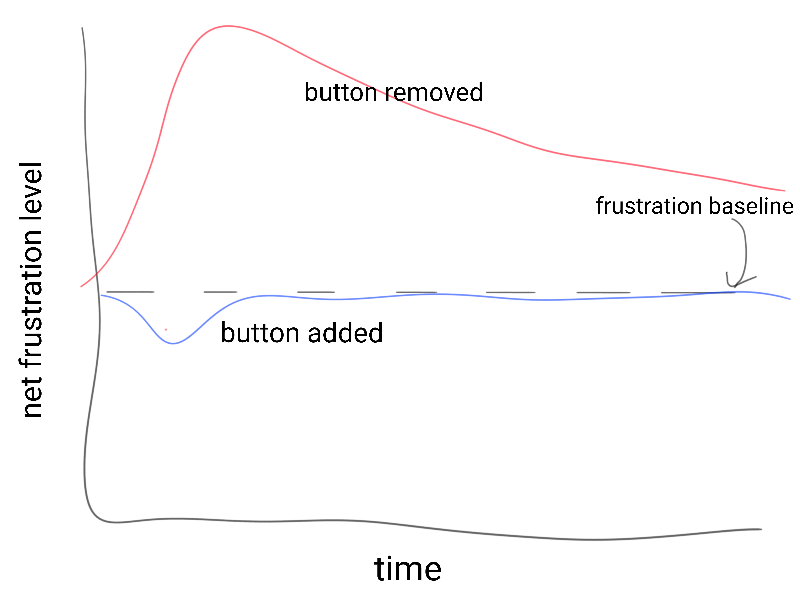

There’s a weird imbalance with changes that act as force multipliers, though. Think of our Bugzilla example. What if the original process had required multiple steps and took 10 seconds, but the update refined that to a single click? The ratio of time savings would have been the inverse: a 90% decrease instead of a 10x increase in clock seconds. However, the same transform would not have applied to the frustration level. We definitely would have noticed that the process for claiming a ticket now took one step instead of an inelegant and inefficient set of actions, and we would have liked it, creating a bump in satisfaction. But it would have been a smaller bump in satisfaction compared to the major spike in frustration we actually experienced. And both of those changes would have eventually reverted back to whatever baseline existed, as the status quo became normalized, for better or for worse.

Impact on frustration levels whether happy button was added vs removed

You better be very careful about preventing the introduction of frustrations and of fixing their root causes quickly when they do appear, because those stressors can leave unhealthy artifacts that can affect your team and its members in increasingly unhealthy ways. And I guess that “frustration baseline” should really be adjusted in the graph, because that bastard can be a moving target in many organizations where engineers feel like they are the regular recipients of new and ingenious methods to waste their time and decrease their effectiveness.

So, what ended up happening with the Bugzilla button? Magically, the “assign this to me” button reappeared a few weeks later. Well, it wasn’t exactly the same button. I seem to recall it now took two clicks, as opposed to the original one-and-done button, but two steps was still much better than click-scroll-type-curse-scroll-type-curse-click-curse-update. I asked my buddy on the FreeBSD kernel team if he had maybe said something about it to his boss. “Maybe.”

The FreeBSD kernel team reported to David Filo, one of the company’s founders.

I don’t know how much actual work returning the button required, but I think it’s safe to say that it was much less than 168 full engineer hours.

I’m not trying to bag on that dev team at this point. I don’t know how the original button ended up getting removed, but while it was definitely a very important oversight, it was clearly a reversible oversight. Everyone should be afraid of those cultural and management dysfunctions that made a team think they could, should, or had to leave a serious inertial generator in place until whenever, instead of immediately saying, “oh, wow, sorry about that, that seems important, we will fix it right now…” But that’s a dysfunction for another post.

Force multipliers, whether of the human or technical variety, create time and reduce the mental taxes engineers pay to do their job. The human variety will often be taken for granted if they do a particularly good job, so the managers and teams who want that magic need to watch for it and nourish it. And if an inertial generator pops up, prioritize on limiting its impact. If you refuse to tolerate ongoing and egregious wastes of your engineers’ time and energy, everyone wins in the long run.