If you can’t measure it, you can’t manipulate it

Cop-turned-public school teacher Pryzbylewski learns “juking the stats” happens everywhere

In the classic HBO series The Wire , the police brass spend more of their time on politics than on anything else. This obsession with optics often takes the form of what the rank-and-file characters refer to as “jukin’ the stats:” manipulating numbers and statistics by various methods to meet arbitrary targets, basically to create the impression that situations are improving or people are doing a better job than they actually are.

The term “jukin’ the stats” has made a lot of headway into the vernacular because the practice itself is so prevalent in so many fields. It is a spin on Campbell’s Law, formulated by social scientist Donald J. Campbell. Any metric used to make decisions becomes subject to distortion and manipulation and can then, in turn, distort and manipulate the object or goal it was meant to measure. As soon as someone with power cares about a measurement, someone now has incentive to game that number for their own benefit, at the cost of an accurate picture of the measurement’s original objective or goal.

In addition to “juking the stats,” a number of rules and ideas also overlap with Campbell’s law. One of these adages, named for economist Charles Goodhart, a contemporary of Campbell, correlates strongly with Campbell’s law. Goodhart’s law posits, “Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.”

The full clip above actually demonstrates one of the classic examples of Campbell’s law: how the use of standardized testing of students to evaluate the schools themselves led to schools that “teach the tests” or manipulate other statistics, like dropout rates, that impacted the schools’ performance rankings. The schools and teachers were ultimately, if unintentionally, pressured to spend their time in the classroom making sure the students would perform well on the standardized tests rather than making any actual attempts at educating them.

Of course, this blog focuses more on running production services, and no one in the tech industry would do such a thing like manipulating indicators or fudging measurements. Oh wait, yes, they would, sometimes to the extent of building entire companies on a foundation of juked stats. (Theranos, anyone?) Usually, however, the effect happens on a smaller and less visible scale.

If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it.

- I don’t know who said this first

Let’s look at some ways engineering teams use and abuse, and sometimes are used and abused by, statistics and metrics. Again, remember Campbell’s law: the more decision-making power associated with a given measurement, the more likely that measurement will be manipulated, and also, the more likely that it will end up negatively distorting the original goals.

Making P0s into P1s

No one will notice

If you can’t improve it, pretend it didn’t happen.

- me

I was in a team meeting once where the manager rationalized downgrading a severe (P0) outage into a less-severe P1 outage because we had used up our budget of P0s for the quarter. There’s a first time for everything. (This particular meeting was not the first time for anything.)

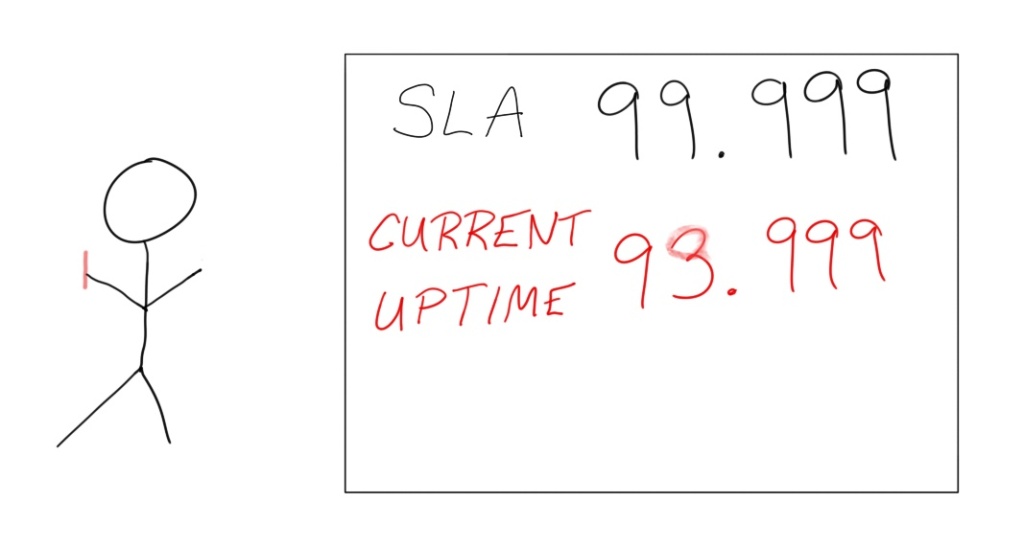

Ever wonder why there always seems to be a noticeable lag between when a service starts having noticeable issues until the issues are acknowledged on their status page? Few, if any, companies with financially-backed contractual Service Level Agreements (SLAs) tie their real-time service monitoring to their customer-facing status page, for two main reasons. First, and yes, this situation happens: your actual production service could be completely healthy, but if your monitoring system has an issue, you don’t want to end up being on the hook to pay customers for an outage that didn’t even happen. Second, in parallel to the conversations had by the engineers working the incident on identifying the issues and how to fix them, another set of conversations is taking place, fed by information from the engineering side, on what to tell customers and when. If lines can be fudged as to whether customers really saw an “outage” or only a slight “degradation of service” that doesn’t really constitute an SLA breach… Honestly, often, the customer who bothers to argue with their customer success rep will get the SLA penalty payout. Consider the dollar value of your time carefully.

Mistaking Quantity for Quality

If you’re measuring it, are you actually improving it?

- also me

What’s the first thing you would do if your manager announces that job performance measurement for engineers will now be based, at least in part, on metrics around the number of pull requests merged or the number of lines of code written?

I mean, I personally would tell that manager how full of shit that idea is because it’s going to lead to a large number of small and pointless pull requests, which will waste reviewers’ time, and the proliferation of verbose code which does not improve in any way on the more concise code that had been written the week before this edict. If you’ve ever had to traverse at least three abstraction layers of objects while trying to debug a python app which was just a wrapper for kubectl, you’ll know that less code is very often more not-awful than more code.

These metrics can also have outsized negative impact on already underrepresented or marginalized people in tech. The time investment that an engineer spends making the code change and opening the pull request doesn’t end there. That engineer has to respond to any comments, questions, or requests for additional changes, until the PR is either merged or abandoned. That takes time. and if some engineers are the targets of bias, unconscious or not, from their colleagues, the impact of having to spend extra time defending their work can take a real toll, both in terms of total output and in their morale and likelihood of staying at that company, or even in the tech industry as a whole. This paper addresses gender bias in open-source software; employees at some large companies have tried to make the same assessments internally and have not met with much support from their management.

So, if you use an already-arbitary metric that will be used in a way which directly impacts a person’s career without recognizing, let alone correcting for, the potential for bias and the time/energy/morale tax placed on the targets of that bias, just GTFO. The next thing I would do after delivering this spiel would be to start working on finding myself a new manager. Sure, there’s a very good chance these metrics, which are glaringly ignorant both of how to produce quality software and of how not to sabotage what, if any, half-assed DEI initiatives the company may have, were shoved down the management chain from on high. But people in that chain who should have known better either did not speak up or… agreed?

That new manager I’m going to look for? At a different company.

All of This Has Happened Before

If you can’t improve it, measure something else.

- still me

A common scenario arises in engineering teams after either a series of customer-impacting issues or a major outage: how do we prevent it from happening again? One of the most common answers: “Let’s monitor something!”

What happens next depends on a number of factors. Let’s assume that the engineers choosing the metrics are competent and knowledgeable, which takes one major factor off the table.

If this meeting takes place in a company culture where product quality is prized, where honest conversations are encouraged instead of openly or tacitly discouraged, and where the perception of doing a good job correlates strongly with actually doing a good job, then this team has a good chance of settling on some metrics that may not be a panacea for their quality and reliability struggles, but will at least move them in a better direction as they continue to iterate toward more mature and disciplined engineering practices.

However, if this meeting takes place in an engineering culture where company politics take precedence over everything else, the chosen metrics will probably correlate more strongly with what the team thinks the management chain wants to see than with the actual health of the software. In fact the very act of identifying action items in an incident review is often perceived as an indicator of how “effectively” that incident review was conducted. It’s quantity over not just quality, but sometimes even relevance. One time my team had an action item assigned to it for an outage we had never heard of, from an incident review meeting we had not been invited to, and to monitor a component that the team had not owned for years. That particular meeting was not about understanding an outage in order to reduce the probability of its recurrence. It was about making the people involved look like they were Doing Something (preferably while throwing some of the blame-free blame on other teams, whether they deserved it or not). And that outcome was very much a reflection of the company’s culture as a whole.

What’s the best indicator or metric to use for tracking how much an organization manipulates the indicators and metrics it uses? Trick question. Even if the correct measurement was introduced into a highly-politicized, opaque environment, it would immediately be mutated beyond recognition.

I’ve just gone over a few of the broad ways metrics in an engineering organization can be (and have been, more times than I can count) misused, distorted, or outright twisted. I don’t really offer any solutions, either. In fact, the presence of these measurement manipulations serves as a pretty strong lagging indicator of how corporate politics take precedence over making positive improvements in both the engineering teams and their product output.

Choosing the most effective indicators for positive, beneficial goals requires internal transparency, honest conversations, and a recognition of the many factors, both technical and human, that impact and underpin a system’s health and a metric’s values.