Part 11 of experiments in FreeBSD and Kubernetes: Bootstrapping the Kubernetes Control Plane

Table of Contents

Recap

In the previous post in this series, I created my Kubernetes cluster’s virtual machines, the cluster certificates, and client authentication files, following the tutorial in Kubernetes the Hard Way. I also set up an authoritative DNS server to handle my local zone on the hypervisor, as well as creating firewall rules to load balance across the three controller instances. Now I’m ready to bootstrap etcd.

A few details for reference:

- My hypervisor is named

nucklehead(it’s an Intel NUC) and is running FreeBSD 13.0-CURRENT - My home network, including the NUC, is in the 192.168.0.0/16 space

- The Kubernetes cluster will exist in the 10.0.0.0/8 block, which exists solely on my FreeBSD host.

- The controllers and workers are in the 10.10.0.0/24 block.

- The control plane service network is in the 10.50.0.0/24 block.

- The cluster pod network is in the 10.100.0.0/16 block.

- The cluster service network has the 10.110.0.0/24 block.

- The cluster VMs are all in the

something.localdomain. - The

kubernetes.something.localendpoint forkube-apiserverhas the virtual IP address 10.10.0.1, which gets round-robin load-balanced across all three controllers byipfwon the hypervisor. - Yes, I am just hanging out in a root shell on the hypervisor.

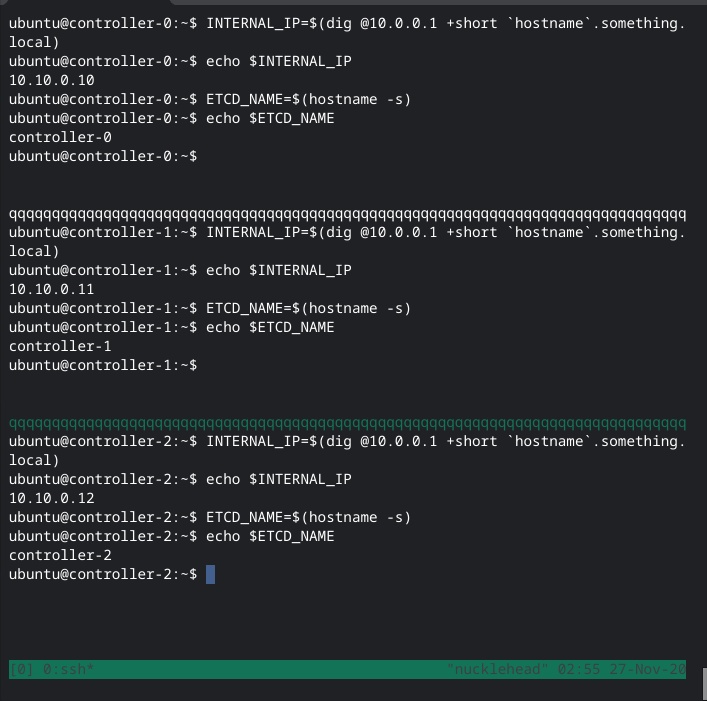

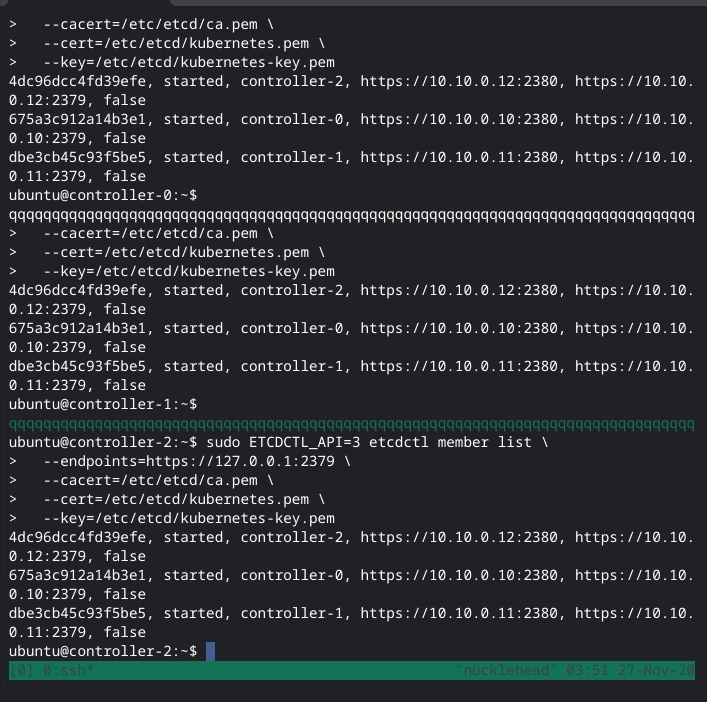

Bootstrapping the etcd Cluster

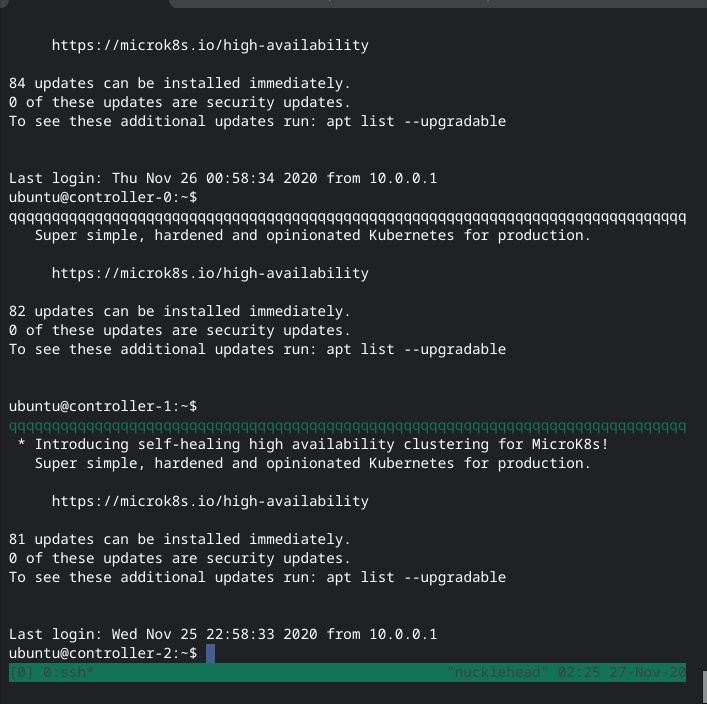

First off, I fire up tmux, create three panes, then google to figure out how to split them more or less evenly. Then I spend another five minutes trying to fix the term type because I’ve finally lost patience with getting rows of q instead of a solid border. However, nothing I try seems to fix it and I can’t find anything on the net, so this is what my window looks like and why am I reading /etc/termcap in the year 2020?

And done.

Bootstrapping the Kubernetes Control Plane

I didn’t read the section on certificate creation closely enough, so I missed the part about how the Kube API service IP should (must?) be part of a dedicated block for control plane services. My current kube-apiserver endpoint is currently in the same block as the VMs, so I will use 10.50.0.0/24 for the service block. I quickly redo the virtual IPs I added to the controllers and the ipfw rules on the hypervisor, then update the DNS record for kubernetes.something.local to 10.50.0.1.

Rabbit Hole #3: Load Balancing Revisited

After I set up the nginx reverse proxy with its passthrough to kube-apiserver’s /healthz endpoint on each controller, I wondered a bit if I should revisit the cut-rate load balancing I had set up using ipfw and VIPs. While it spreads the requests to the Kubernetes API’s virtual service address across the three controllers, it has no health check support to make sure it’s not sending a request to a server that cannot respond, and ipfw does not support such a thing.

I consider a few options:

- Create a service on the FreeBSD hypervisor that runs the health check for each backend and then updates the

ipfwrules as needed; requires maintaining another service and also requires ensuring I don’t mangle my firewall in the process. - Instead of using a virtual IP address for the API endpoint, convert it to a round-robin DNS record. Using a custom service health-check like the one mentioned above, the service could update the DNS zone to remove a failed backend host. This option would actually be worse than updating

ipfwrules, because not only because I would risk mangling my DNS zone. I would also have to deal with time-to-live (TTL) for the DNS record, which requires balancing a low TTL which carries frequent DNS lookups versus using a longer TTL, which can make the time to fail over unpredictable for clients. Round-robin DNS is clearly not a better option, but I mention it because round-robin records often buy simplicity of implementation at the price of multiple headaches down the road. - Add a reverse proxy service on the hypervisor, such as

nginxorhaproxy, to query the/healthzendpoint on each backend and avoid sending incoming requests to servers that are unhealthy. Unlike theipfwround-robin, this solution runs in user space rather than in the kernel, which means it adds a performance hit and also requires managing another service. - Use CARP (Common Address Redundancy Protocol) for failover. While I had originally thought I could use CARP on the FreeBSD host to handle some form of failover, it became clear that was not an option, because CARP has to be configured on the endpoint servers themselves. However, I could use the Linux analog

ucarpto create server failover between the controllers.

I ended up not setting up CARP for a few reasons:

- Unlike FreeBSD’s implementation, which runs as an in-kernel module, Linux’s

ucarpruns as a service in userland. In other words, it requires managing yet another service on each of the controllers. - Neither CARP implementation can monitor a specific service port for liveness. Failover only occurs when the host currently using the configured virtual IP address stops advertising on the network.

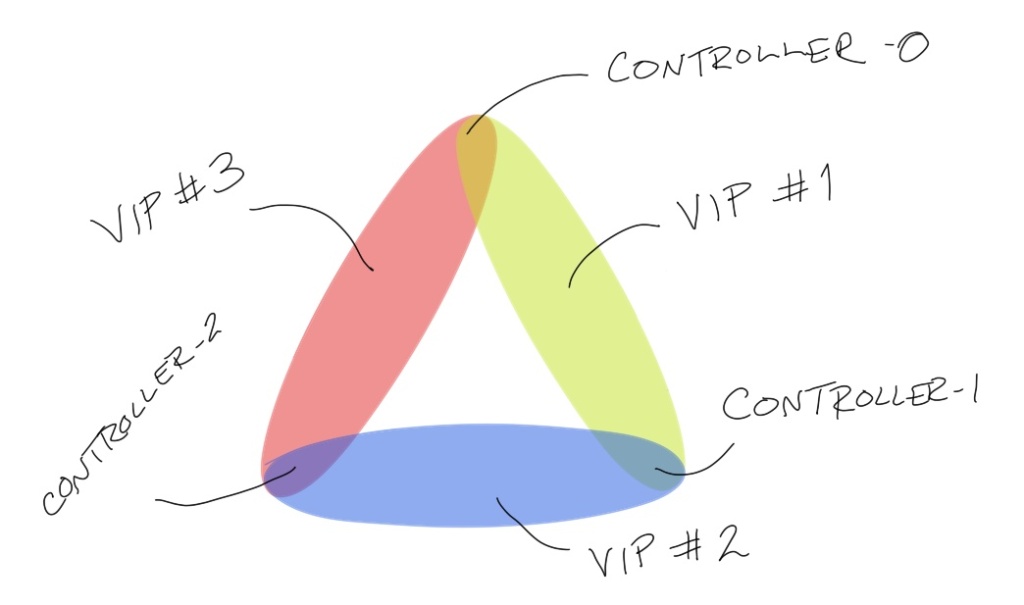

ucarponly supports pairs of servers for a given virtual IP address, while I have three controllers. I could do something like create three CARP groups, one for each possible pair, and then use those for the endpoints in theipfwfirewall rules. However, that doesn’t really solve the problem of a VM advertising on the network but not servingkube-apiserverrequests for other reasons. But I had to look at CARP again anyway.

Diagram showing what a 3-way failover could look like with CARP when you can only have two servers in a group

In the end, I decide not to implement a truly highly-available configuration because I’m not creating a production system, I already have more than one single point of failure (SPOF) so what’s one more, and I was hoping for a more elegant or a more interesting solution. I’d probably go with setting up a reverse proxy to use as a health-checking load balancer on the FreeBSD hypervisor if I really needed high availability in this scenario.

Verifying the Control Plane

After escaping from that rabbit hole, it’s time to see if I set up the control plane correctly.

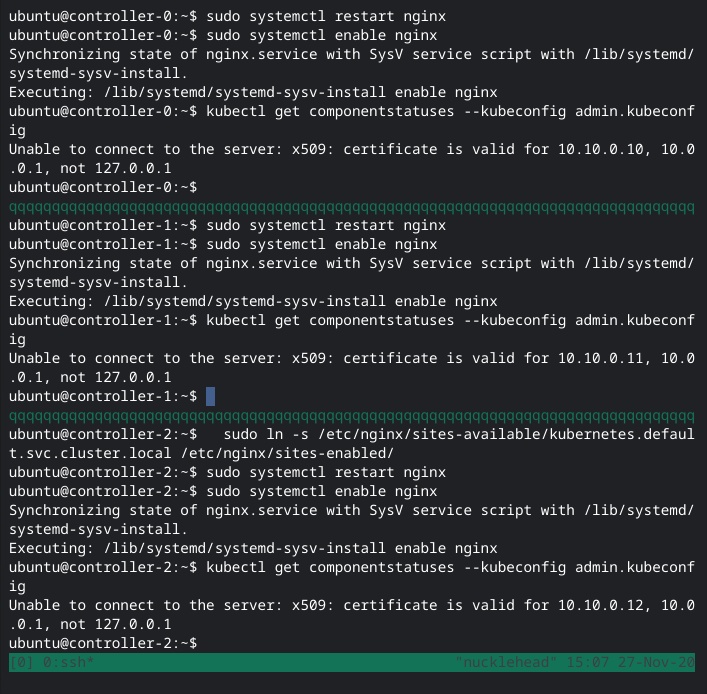

Well, that’s a no. It looks like I somehow missed adding the localhost endpoint when generating one of the certificates (probably the API server’s). And come to think of it, I also forgot to update the certificates when I changed the kubernetes.something.local IP address.

I regenerate kubernetes.pem and then copy it around. Both kube-apiserver and etcd use it, the latter for authenticating peer connections from the API server. I restart the services and… still get the error. I double check the generated cert with openssl x509 -in kubernetes.pem -text and yes, the hostnames are all there in the list of Subject Alternative Names (SANs).

<script src=”.js”></script>

Except it’s odd that the kubectl error tells me the only valid IP addresses are 10.10.0.1[0-2] (depending on the controller) and 10.0.0.1, the default gateway configured on the VMs. Sooo… I go digging. It looks like kube-apiserver’s default path for certificates is /var/run/kubernetes, which I had created per the tutorial. Sure enough, there were two files there which I had not created: apiserver.crt and apiserver.key. And when I ran the openssl x509 ... command on apiserver.crt, it only had two configured Subject Alternative Names: 10.10.0.1[0-2] (depending on the controller) and 10.0.0.1.

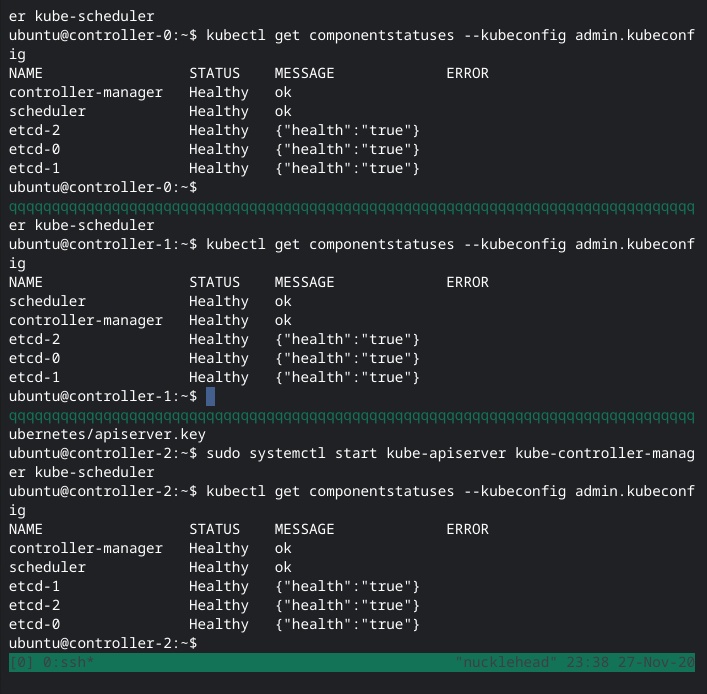

I delete those files, restart kube-apiserver and as I expected, it regenerates them, but they still have the same useless SANs. So, I stop everything again, and copy over the damn kubernetes.pem and kubernetes-key.pem (the ones I had created) from /var/lib/kubernetes to /var/run/kubernetes with the appropriate file names, fire everything up (again), and yay, shit works now, let’s move on.

I configure kubelet RBAC, skip the section on creating a load balancer in Google Cloud since I have my ipfw rules in place and, you know, not in GCP. I test my fake load balancer endpoint, and everything works.

<script src=”.js”></script>

In the next installment, I’ll start off by bootstrapping the worker nodes and maybe finish building the cluster, depending, as always, on the number of rabbit holes I can’t resist.