How Agile development in practice often seems more like loosely organized chaos rather than coordinated acceleration

We have probably all heard Aesop’s fable about the tortoise and the hare. The rabbit, so sure his superior skill will win the race against the tortoise, stops in the middle to take a nap while the tortoise moves slowly but consistently toward the finish line.

Slow and steady only wins the race if you’re going in the right direction. The same goes for fast and/or arrogant.

I will state right off the bat: I am not an expert, or anything close, on sound, sustainable, and successful Agile practices, because I’ve never seen them firsthand. Part of the reason probably comes from my background, predominantly in SRE/ops roles, where I was always writing code, but, while some SRE teams do stick to (or say they do) Agile principles, generally in the form of scrum, doing so has always felt like trying to shove a square peg into a round hole when I’ve been on one of those teams. That topic deserves its own post but it’s not the focus of this one.

I have worked on product software development teams, I’ve been in planning meetings, estimated story points, gone through Kanban training, all of that, but I’ve never had the privilege of witnessing an engineering organization that was purportedly adhering to Agile principles and that seemed to produce quality software on a regular schedule while maximizing developer productivity and “happiness.” (Using air quotes there because I don’t know what makes every developer happy, but I’m going to guess that more than a few would be happiest to get paid doing whatever they wanted whenever they felt like doing it.)

If I had to choose one term to describe my impression of Agile, at least as I’ve generally seen it practiced firsthand, I would choose “Brownian motion.”

Lots of motion, but in which direction?

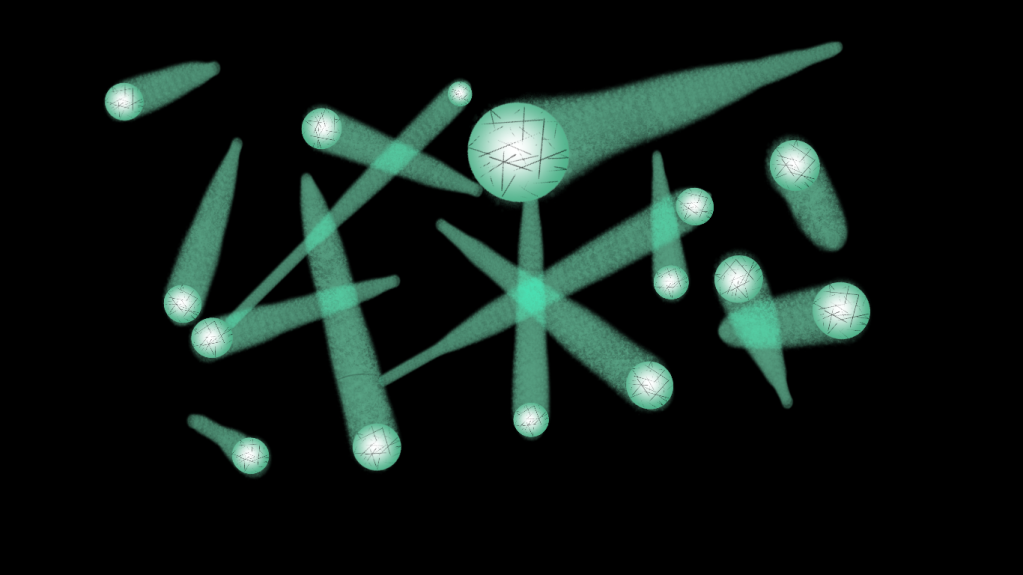

Okay, before we talk about the Brownian motion bit, let’s talk about how I visualize effective engineering teams: as a Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC), in which a group of particles have been coerced to assume a single, shared quantum state. All right, that analogy doesn’t actually fit perfectly, because the particles (developers) do not and should not necessarily act in exact synchrony, and not much actually happens in a BEC because it generally requires cooling the particles to such a low temperature that they don’t actually do much at all. I would think, though, that a team of engineers should be working toward a shared end state or goal.

Instead, too often, Brownian motion provides a more accurate depiction: after the sprint planning meeting, the devs all run off to do stuff! That’s the point, right? Well, not if they’re all running off in random, unaligned directions. A bunch of individuals each moving at high velocity does not necessarily mean that the team is moving at a high velocity if those individual velocities cancel each other out. If you and I stand back to back, and we each start walking forward (from our individual perspective) at the same same speed, yay, exercise! except our net velocity using the starting point as the frame of reference is zero. And if, say, we’re both trying to pull the same wagon, it’s not going to go anywhere, is it?

This pattern may not be easy to spot within a single sprint or even a small number of sprints. At one job, I automated the demos for the application. New functionality with its own API endpoint came out, so I automated that feature’s configuration. After the very next sprint’s release, that automation broke. That API endpoint had existed exactly two weeks, because it was not compatible with what had been a longer-term project to rework the API’s permissions scheme, released the following sprint.

This example wasn’t a case of intentional retirement: the developer working on the new API endpoint was pretty new and wasn’t involved in the discussions of the API changes and thus had followed the extant pattern in the main branch at the time. Lack of effective communication and of thinking about the big picture of all the balls currently in flight (namely overhaul of API permissions) leads to wasted, nullified time. I agree with this blog post that makes the point that robbing software engineers of context or thinking that executing the story properly does not require awareness of the greater context will generally sabotage the improvements you think using Agile is supposed to reap. For junior or newer engineers on a team, when full knowledge of that context and its implications is not really a possibility, someone should be working with them who can put those pieces in place.

Of course it’s not realistic to think that APIs or anything else in software should never change (conversations about API versioning aside), but two weeks makes no sense, particularly since the situation here was not intentional, let alone evaluated beforehand and deemed acceptable.

Even if you think you have good alignment within each sprint, are you aligning your goals consistently across sprints? I don’t know if anyone has ever created an accurate “sprint vector” for measuring velocity and direction, but maybe that should be a thing. No, counting completed story points does not suffice, because, for a start, it assumes the stories were well-written, accurately captured what needed to be done, and aligned with other active stories and epics. For any such sprint effectiveness or success measurement system, all the stakeholders need clarity and self-honesty, in addition to a general atmosphere of psychological safety.

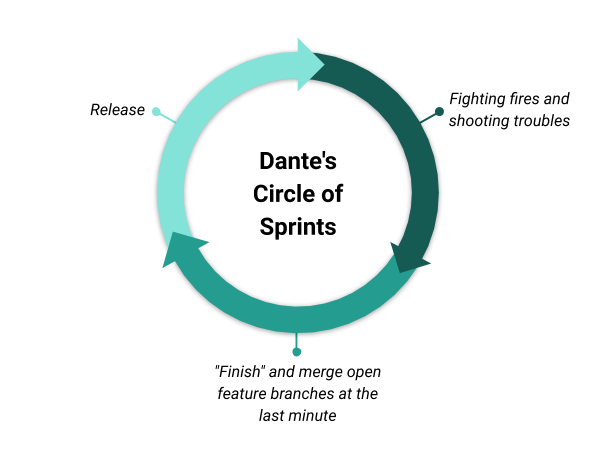

Another example, one I see and hear about pretty frequently, takes the form of predictable cyclic disruptions. These cyclic disruptions are called releases. To be fair, the actual disruptions come right after the release, because “Hot-Fix Thursday” invariably follows “Release Wednesday.” (Granted, there’s a good chance that “Release Wednesday” had already been rescheduled to “Release Thursday” because of delays, leading to “Hot-Fix Friday,” which has a pleasing consonance.) Teams rush to finish the sprint’s stories and run out of time, but it all goes into production anyway. Then the team spends the first half of the ensuing sprint troubleshooting, debugging, pushing fixes, and now they don’t have enough time to finish the full slate of that sprint’s stories, at least not properly. Lather, rinse, repeat.

“Finish” and merge open feature branches at the last minute -> Release -> Fighting fires and shooting troubles ->](//assets/images/2020/09/untitled-drawing-2.png?w=597)

While that cycle’s non-stop spiral of disaster can only continue to exist because of multiple factors, held together by a generous application of normalized deviance, to me it’s just bat-shit nonsense. Yes, bugs will always happen, but this system seems to occupy a strange reality that ignores that inevitability while simultaneously actively maximizing insect reproduction. And what this pattern most definitely does not maximize is engineering velocity nor engineer satisfaction.

Google SRE will tell you that error budgets would short-circuit this cycle. I agree. I hope to work in an org someday with the maturity and honesty also to agree and to follow through, even when it may mean promised features get delayed by months. That trade-off can be a hard sell in many startups.

At any rate, the lack of alignment or the series of failed sprints, which either did not include all of the planned stories or created a catastrophe (or 12) after release, lead to really poor engineering efficiency. People are running around, spewing code out like crazy, but everything is always behind schedule. Many other factors also play into that equation, perhaps overly optimistic story points (although if that’s a pattern that doesn’t get addressed, maybe it should be), a code base or architecture oozing with technical debt that impacts your engineering velocity like molasses, and otherwise unrealistic expectations overall of how much the engineering team should be able to deliver.

Lots of sprints going lots of different directions

I’m not taking the stance that no organization can or actually does practice Agile methodology “correctly,” in a way which reaps its promised benefits and maximizes production and engineer satisfaction, although maybe I’m mistaken when I think someone in one of those teams would be so constantly blissed out, that would be the first thing they told you about themselves when you met: “I work on a team that gets Agile right!” And I’m certainly not calling for a “return” (air quotes because too many SREs are still seated at the bottom of Niagara Falls even in orgs claiming they’re Agile) to waterfall process. But it is certainly very, very easy to do Agile… suboptimally. So easy, in fact, that the tales about that outcome seem to be far more prevalent than ecstatic success stories. But if so many “Agile” implementations are inherently broken, then either the system itself is broken or the people implementing it are. (Or both.) And yes, I’d even go so far as to say a broken Agile process probably bears a strong likeness to the organizational culture that generated it.

Actually, come to think of it, maybe that near-motionless Bose-Einstein condensate is the right analogy after all.

tl;dr

- Make sure your various

particlesdevelopers have some alignment and enough of the greater context (other near-future pending changes or work in progress, etc.) not to step on each other’s toes or put time into something that will just have to be redone almost immediately, unless a very good need exists to take the human time hit - If every sprint looks like “rush to get stories done, release, fix broken shit half of the following sprint” played over and over, you’re probably doing a lot of somethings wrong

- Pragmatism > dogmatism. If the gospel isn’t working for you, try some apocrypha