(Hopefully) Practical advice for people who want to learn about Kubernetes

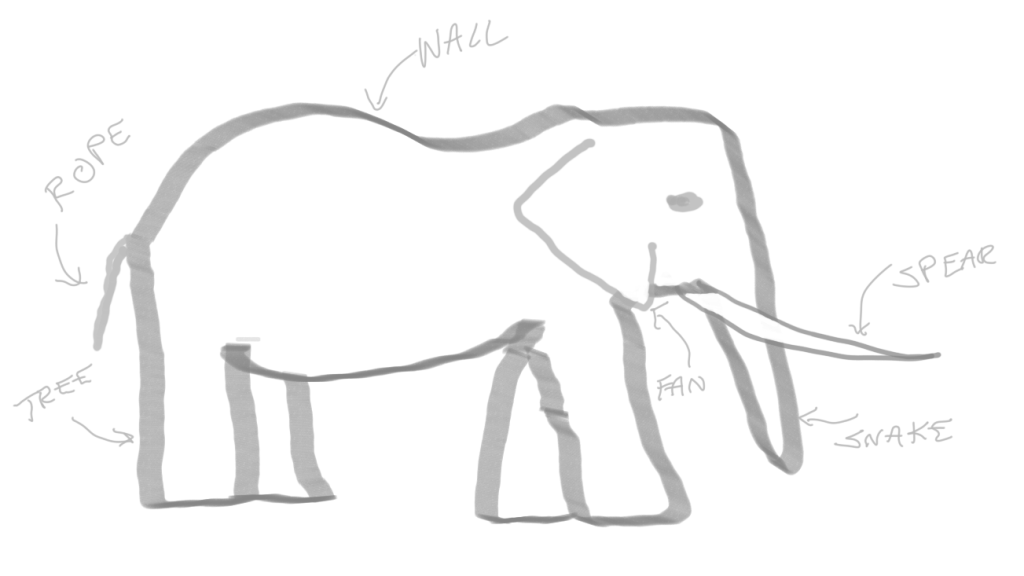

A famous ancient Indian parable tells the story of a group of blind men who come across an elephant for the first time. One man touches the trunk and thinks the animal is a large snake. Another man feels an ear and thinks it’s a large fan. One feels a leg and thinks it’s a tree trunk. The men who touch the tail think it’s rope, the tusk a spear, and the animal’s side is a wall.

This parable always comes to mind when I hear people, specifically engineers, say they “need to learn Kubernetes.” First of all, I wonder how many of them mean they have an actual forcing factor, or if they just “need” to the way I “need” ice cream sometimes.

Either way, I also wonder which part(s) of the elephant they think of as Kubernetes, or at least as the parts of Kubernetes they need to learn.

This post is a guide to what I think of as common basic starting points for learning about Kubernetes, who might most benefit from or use a particular focus, and where to find more information.

Contents

- Kubernetes Concepts and Terminology

- Cluster Creation

- Deploying an App

- Writing and Containerizing Apps For Kubernetes

- Extending and Integrating with Kubernetes

Kubernetes Concepts and Terminology

Kubernetes uses a lot of custom terms and acronyms that anyone starting off will need to learn. You’ll want to have at least basic familiarity with many of these before you start a tutorial, although after you have some hands-on experience, understanding the jargon and following documentation becomes easier with time.

Resources

- https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/overview/components/

- https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/an-introduction-to-kubernetes

- https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/overview/working-with-objects/kubernetes-objects/

Cluster Creation

Before you can tinker with a Kubernetes cluster, you will probably need to create one. Options, as well as which tools you could use, depend on the environment and resources at hand, whether bare-metal (which can even be a couple home PCs or laptops or even Raspberry Pis), a cloud provider, or a virtual environment running on a single computer.

For people who want to learn about the fundamental, low-level components of a Kubernetes cluster, you might want to build a cluster completely from scratch, either on the cloud or a couple computers you have lying around.

https://twitter.com/fuzzyKB/status/1300943852719595521

You might think your best option if you want to bring up a small cluster for experimentation quickly would be to try a cloud-managed Kubernetes service. However, the free-tier pricing here is confusing at best. Some free-ish/inexpensive options*:

- Google Kubernetes Engine (GKE) in Google Cloud Project (GCP)

- Control plane: one free zonal cluster control plane (the set of backend services that every cluster needs) per GCP project

- Nodes: GKE does not support running on the GCP free-tier F1-micro instance type. You will have to use a larger node size, which won’t be free.

- Elastic Kubernetes Service (EKS) in Amazon Web Services (AWS)

- Control plane: $0.10/hr, no free tier option

- Nodes: their free tier offers 750 hours/month of t2-micro Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) instances for one year.

- Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS)

- Control plane: free by default

- Nodes: 750 free hours/month of B1S virtual machines for the first year, which you can use for very small cluster nodes.

- Digital Ocean Kubernetes

- Control plane: free

- Nodes: Standard compute prices.

- IBM Cloud Kubernetes Service on IBM Cloud

- Control plane: Free trial cluster for one month.

- Nodes: Free 2CPU/4Gb worker node for one month.

Note that you may be responsible for disk storage, load balancer, or network traffic costs, depending on the cloud provider and your exact usage. Unfortunately, cloud pricing documentation is generally confusing, so be sure to watch check your usage costs frequently to avoid surprises.

If you have a Linux computer laying around, you might want to try using a tool like k3sup to create a lightweight Kubernetes cluster locally.

*Free tier offerings described here are current as of 08-2020 but may change at any time. Check the relevant cloud provider documentation for current offerings.

Deploying an App

I assume this is what many, if not most, developers mean by “learning Kubernetes,” at least initially. Also, no matter what you need or plan to do with Kubernetes, you still almost certainly want to start with this basic skill and do it using the basic standards, namely kubectl and resource manifests in YAML.

Ironically, though, the tooling, configuration formats, and process of this most basic form of interaction varies wildly across different organizations using Kubernetes, as new tools and abstraction layers and methods for configuration management proliferate, including Helm, operators (which themselves must also get deployed; more on them later), more general infrastructure management tools like Terraform or Pulumi, or custom wrappers and automation, plus a growing suite of tools focused on continuous integration and deployment.

Resources

Writing and Containerizing Apps For Kubernetes

Developing for Kubernetes can mean many different things. Let’s break down some options.

Stateless or Environment-Agnostic Apps

For most application developers, in general, they probably do not need to learn anything particularly special about writing apps for deployment on Kubernetes clusters. Many stateless applications, from web servers to frontend apps to most backend services, have been lifted and shifted into Kubernetes deployments with few, if any, modifications. As long as the container build follows some best practices for manageability and playing nice in a multi-tenant system, you don’t really need to learn any magic if your focus is on moving from writing apps for “bare-metal” or other server-based deployment environments to writing the same types of applications to be deployed on Kubernetes clusters.

Stateful Applications

Stateful applications, like databases and other services which require data persistence, prove more complicated. In some cases, they may not require modification as long as sufficient service discovery and storage options exist in the cluster targeted for deployment. Stateful applications with more advanced or specific storage and networking needs may require customization or porting.

Resources

Extending and Integrating with Kubernetes

Powerful extensibility and the opportunities for customization are major factors for Kubernetes’ popularity and widespread adoption. Depending on where your interests or requirements fall, you may be looking to focus on one of the following areas.

Interface Plugins

While a Kubernetes cluster is, at least for the people who just need their apps to run somewhere, a good infrastructure abstraction layer, the logistics of getting that abstraction layer to function in various environments requires some glue.

In earlier releases of Kubernetes, environment-specific driver interfaces lived “in-tree,” as part of the main Kubernetes code tree. To decouple the development and code maintenance of the growing number of integrations and to ease porting of Kubernetes to new platforms, teams working on cloud native projects have defined specialized Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) for developers to use to extend Kubernetes device support.

Currently Kubernetes supports three main container interfaces:

- Container Network Interface (CNI): CNI plugins implement and extend cluster networking capability. They can come in several flavors, whether providing environment-specific pod-to-pod routing across different cluster nodes or by modifying basic cluster networking, sometimes of another CNI, to add, for example, NetworkPolicy support for declaring allowed and blocked network traffic in the cluster.

-

Fun fact: Docker does not actually implement the CRI specification. Instead,

containerdacts as a shim on most nodes that use Docker as their runtime. containerd can also operate as a thin container runtime without Docker. - Container Storage Interface (CSI): CSI plugins provide an interface between a Kubernetes cluster control plane and a storage layer in the environment the cluster runs in. For example, a cluster running in AWS might support using AWS Elastic Block Store (EBS) volumes for persistent storage by using the appropriate CSI plugin. (Note that support for AWS EBS already exists “in-tree” for Kubernetes, but that code is no longer being updated with new features and support, in favor of a separate, supported CSI plugin.)

Extensions are also sometimes needed for support of some hardware or device classes, including Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) or specialized device interfaces.

Controllers and Operators

Custom Resource Definitions (CRDs) make up another point of extensibility for Kubernetes. If you’ve worked through a tutorial for deploying an application to a Kubernetes cluster, you’ve already encountered some Kubernetes resources: maybe a Deployment or ReplicaSet, a Service, and possibly a ConfigMap, or other standard types that you create and manage through the Kubernetes API.

You can also extend the Kubernetes API by creating Custom Resource Definitions. The possible use cases for CRDs are virtually endless, but let’s make up small example: an email address CRD. A YAML manifest for a resource object of our CRD type EmailAddress might look like this:

apiVersion: my-email-api/v1

kind: EmailAddress

metadata:

name: some-person

namespace: emails

spec:

firstName: Some

lastName: Person

address: someperson@example.com

Creating a CRD object alone doesn’t do much. It does store the object in the cluster’s backing store, but without some piece of software watching for it, the object’s existence does not trigger any additional action. You could just use a CRD as a simple key-value database, with the kube-apiserver and the backing store handling data persistence, although this model would not scale well and could eventually impact general cluster performance.

If we actually want to use CRD objects to do something, we want a controller to manage the lifecycle of our EmailAddress objects. For example, if we wanted to use our EmailAddress objects to track subscriptions for a mailing list (please don’t do this), we might write a controller that sends a welcome email for new EmailAddress objects (please don’t do this). The controller may also track another CRD for each newsletter edition, handling compilation of current addresses and sending the email (please don’t do this).

Operators are a special class of controllers. Operators also use one or more CRDs and also run a control loop to handle the CRD object lifecycle, but they focus on managing other applications deployed in the cluster. For example, an operator for a RDBMS could, using the values in its CRD resources, deploy and configure the database engine, perform regular backups of the data, and also handle version upgrades.

While other extension types and interfaces with Kubernetes exist, the above list includes those areas that developers who say “I need to learn Kubernetes” are most likely to mean, at least initially. No starting point is really right or wrong, though. Some specific topics may be more immediately useful to you, or more interesting, or an easier jumping-off point to other topics.