Reward the behavior you seek

In the fable “The Golden Axe,” a woodcutter accidentally drops his axe in a river, losing his only means of support. The god Hermes takes pity on him and retrieves a golden axe from the river. The woodcutter replies that it was not his axe, so Hermes returns with a silver axe. Once again, the woodcutter says that axe was not his. The woodcutter only accepts when the god returns with his actual, lowly axe. Hermes, impressed with the woodcutter’s honesty, gives him all three axes.

When the woodcutter’s neighbor hears what had passed and covets the first woodcutter’s new wealth (golden axes apparently being worth quite a lot on the open market), he throws his own axe into the river to try to reap the same rewards. Hermes comes with a golden axe, which the neighbor claims is his. Hermes punishes his dishonesty by depriving him of the golden axe, the silver axe, and his own original axe.

Picture an engineering team. One engineer, either by choice or by mediocre management, spends most of their time paying down technical debt, making proactive improvements to tooling and infrastructure, and building out low-friction ways to add monitoring for production applications.

Meanwhile, another engineer on the same team always seems to get the new, shiny projects to work on: the high visibility features, the highly-touted initiative to “increase engineering velocity” by breaking an application monolith into microservices (to be followed in a year by an equally-touted initiative to merge those microservices back into a monolith), or the fancy new customer product.

Both engineers may be equally skilled and work just as hard, but which one do you think will get the lion’s share of recognition? (If you answered, “The one doing critical glue work,” you either work in a singular organization or you’re seriously out of touch with reality.) And what happens when a new engineer joins the team? Someone who is neither a total narcissist who needs constant adoration nor a masochist who likes to suffer? After seeing the pattern of which engineer gets the public accolades, which behavior do you think they will more likely emulate? The one the team treats as most valuable, of course.

I worked at a company where anyone could nominate a co-worker for demonstrating one of the company “values.” Recipients would get recognized at company all-hands meetings. Let’s see if you can spot a problem here.

Customer success nominates an engineer who helped them troubleshoot a customer-facing problem. Hey, that sounds important, right?

Okay, but what if I tell you that that engineer was the one who pushed the code that broke the service in the first place? Um, well, you don’t want to punish engineers for making mistakes, right? Of course not, but do you really want to give them a t-shirt when they do?

What if I tell you that same engineer had ignored warnings in staging that indicated there were likely performance issues? (In the real-life version of this story, when I sent links to monitoring graphs to ask why we were seeing elevated values for Java heap usage, he replied that the QA team was probably running tests. “Did you ask them?” Crickets. Why didn’t I escalate before the deployment? Ask our common manager at the time what my reward tended to be when I tried to push for the product dev teams to take responsibility for their components’ quality and performance before it got pushed to production.)

The customer success team member who nominated him for helping out during the customer-facing issues did not know the issue’s backstory, though. This recognition system, while not intentionally built to reward “bad” behavior, had no guardrails to prevent rewarding counterproductive habits, either.

Meanwhile, another engineer might deliver a feature that sales can’t really hype to customers and marketing can’t really spin. The code goes live and nothing breaks. Crickets. On the one hand, yes, that engineer did their job and did it correctly. However, an engineer doing troubleshooting, whether for an issue they create in the first place or not, is also doing their job. Again, why does one engineer get recognized and the other does not?

“Human nature” and a number of cognitive biases come into play. We become habituated to things that maintain a predictable state or cadence. We only notice when they stop working, even though that long-lived steady state of reliable functionality required consistent effort behind the curtain to maintain. And of course, new features correlate more strongly with money in the psychology of tech companies. While that association holds some truth, specifically a prominently accepted truth, it’s not the only truth. Quality, service availability and reliability, the ability to maintain engineering development velocity, writing internal documentation: the company cannot bill customers directly for these functions, but try running a sustainable, efficient company without at least some of them. (And many, many, many startups do try to do just that.)

Try this: reward the behavior you seek. And the implicit, but often overlooked, corollary: don’t reward behavior that is, or could easily become, detrimental.

A robust system of positive feedback requires another variable: the difference between publicly rewarding someone compared to privately validating their work.

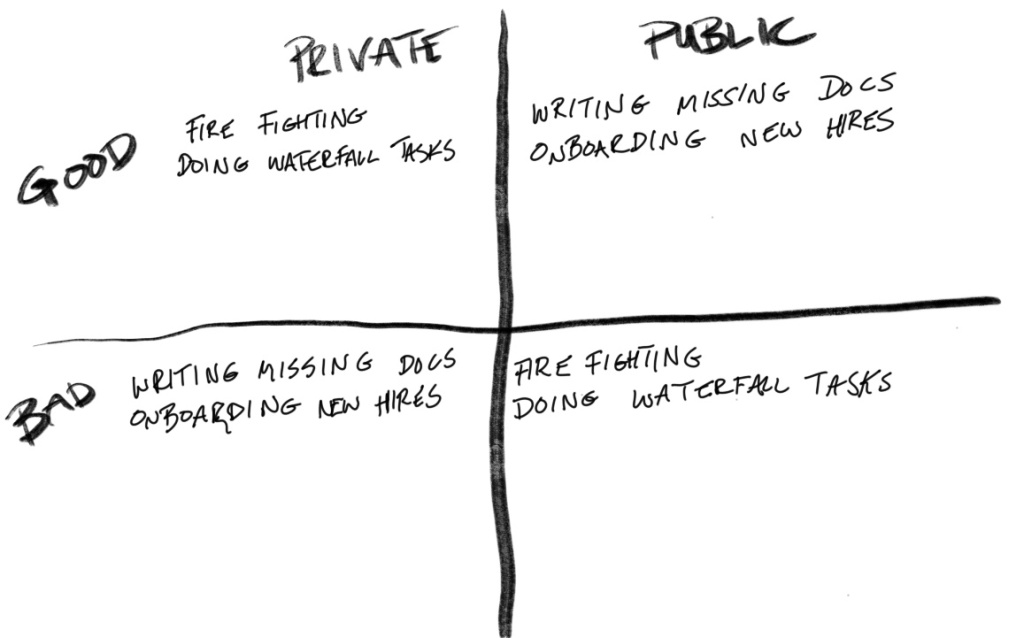

Fire fighting and working on waterfall tasks are best recognized privately. Writing missing docs and onboarding new hires should be rewarded publicly.

When to recognize what kind of engineering achievements

If you want to encourage healthy behaviors, such as writing internal documentation or onboarding new engineers, as a basis for your engineering culture, recognize them in a public forum. Giving only a private thank-you, while better than nothing, can send a subliminal message to the recipient that, yes, they did something beneficial, but it’s not really something to be proud of. And because the acknowledgement is private, no one else gets the message that the team and company deeply value this kind of effort.

However, you still need to be careful here with what you openly reward. If you constantly publicly recognize someone for putting in overtime, for example, you create the expectation, whether you intend to or not, that to get recognized, an engineer has to work much longer hours. Maybe you and your company want and expect that, but don’t come crying to me when your Glassdoor reviews all talk about burnout from being expected to work long hours. If you do genuinely want to create a culture and company with sustainable work practices, call out quality over quantity, value over volume, practical over pretty.

On another side of encouraging healthy efforts, all engineering teams face some amount of work which, while it must get done, should not be presented or encouraged as “normal,” let alone ideal. “Unplanned” work comprises most, if not all, of this category in most organizations, usually in the form of troubleshooting outages or of other “waterfall” tasks that, for one reason or another, were not the result of otherwise standard proactive planning and prioritization, even in a team that claims to follow Agile methodologies.

For any given instance of these suboptimal tasks, obviously the people who worked on them need to be acknowledged. However, they should be thanked privately, to avoid the normalization of disruptive work within the rest of the team and the company as a whole.

Truly healthy organizations will go beyond thanking the individuals left to work on waterfall tasks. Teams genuinely focused on improvement should respond by making real effort to change or prevent whatever cultural or less-than-ideal management or cross-team dynamics ultimately create these “surprise” (which should really surprise no one who pays attention) situations. Working to minimize or eradicate disruptive work not only increases team efficiency and health over time, it represents a much more genuine acknowledgement of engineers and the value of their time and effort than a thank-you note or yet another company t-shirt can.

You also want to avoid creating a culture of “heroes.” Start by minimizing the occurrence of catastrophic events wherein someone needs to save the day. However, even major projects can create breeding grounds for hero worship. Make sure any forms of public recognition note the wider team context of these efforts. Nothing ever gets done in a true vacuum. Even if one engineer did most of the work for a given project, presumably other team members were taking up the slack as their peer’s time was allocated elsewhere. Also remember and remind your team that not all projects are going to be high-profile “game changers,” but someone will still need to do the work. You don’t want to make people who work on smaller, but still vital, projects to feel less important, and you don’t want to encourage the creation of marquee, but ultimately less valuable, work because you’ve sent the message that those projects and the people who work on them are more important.

Unfortunately, this culture of rewarding people who “create” new shinies, even though maintaining old rusties was more critical and valuable to the company, exists all over. And I have countless examples for my time at Yahoo! alone at how it tends to be both a symptom and an accelerator of an unhealthy, moribund, and highly-politicized company culture.

If you want to create a culture where people do the right thing and do it well, start by learning to recognize what the right thing is. Sometimes it’s better to create something new while sometimes, probably more often, maintaining the current system is both more critical and a better investment, at least for the near future. Then make sure engineers who focus on what’s best over what’s exciting get the recognition they deserve, both for the work they do and for the ability to see the difference.

Unless you reward the behavior that provides real engineering and company value, instead of counterproductive behavior, you will probably not end up with a healthy, high-performing culture. First, however, you have to recognize what work truly has value and what does not.